You can learn to sail alongside a group of passionate young sailors who are conserving Venice's historic nautical customs.

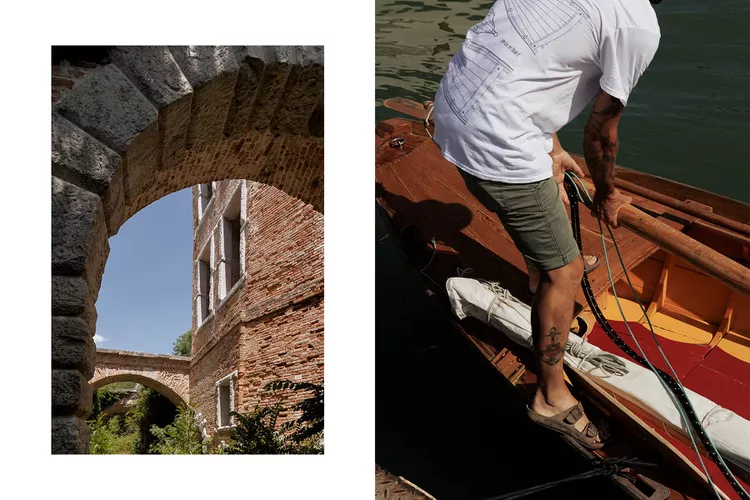

Even locating the sailing and rowing club's office in Venice On Board requires delving deeply into the country's most beautiful city's maritime background. The club is located in the historic Cannaregio boatbuilding neighborhood, where even Google Maps is baffled by the complex network of lanes and canals. I came across this one early spring morning after winding my way there from the Piazza San Marco, getting confused, and having to go back a few times before locating the Rio Della Sense, a remarkably calm side canal next to Venice's last active shipyard. The only person visible at nine o'clock in the morning was a young craftsman with a beard who was planning the hull of an antique wooden sailing boat. I assumed, like Sherlock Holmes, that I had arrived at Venice On Board's headquarters when I noticed a large wooden door behind him that was being watched over by a dozing brown dog.

When I peered inside and discovered what appeared to be a backstage prop room for a production of The Pirates of Penance, the retro nautical ambiance intensified even further. The entire floor was covered in coils of rope, canvas, enigmatic metal objects, and handcrafted replicas of antiquated Venetian sailing vessels. A wall was completely covered with wooden oarlocks called forclem that hung in racks like abstract sculptures; their designs have been perfected over generations to enable for a range of rowing angles. Rows of oars were balanced in the ceiling rafters.

Vogad allay Veneta, or Venetian-style rowing, and vela al torso, sailing on Venice's distinctively shaped topi, small wooden boats that had been in use since the Middle Ages, were two linked arts that I had come here to study quickly. Emiliano Simon, one of the club's three original founders and a sun-bronzed thirtysomething Venetian, was lounging behind a massive desk covered in nautical charts.

He emphasized that since no sailor in Venice could survive without it, the focus of our morning instruction would be on rowing. In the event that the wind dies or you become stranded in an island's lee, you should be able to row. You must have faith in your ability to return home!

A little while later, we were atop the 18-foot topa's deck, which was painted in bright yellow and red. Simon deadpanned, "I will teach you the first lesson to rowing in authentic Venetian style," after dipping his oar and bringing the boat to a gentle stop 100 yards distant, beneath a café. We have an espresso, that is! incredibly early

While we drank coffee, Simon gave us an explanation of why he and his buddies Nicola Ebner and Damiano Ton lotto formed Venice On Board in 2014. The three had a love for the water even though they weren't members of the city's cult-like gondolier or fishing tribes. They hoped to revive Venice's maritime history, which peaked during the Renaissance when the affluent Venetian Republic, also known as La Serenissima ("the most tranquil"), governed a marine empire that stretched throughout the eastern Mediterranean.

According to Simon, until the 1950s, when motorized boats started to take their place, sailing and rowing were significant aspects of daily life in the flooded city. Since then, he lamented, the ancient nautical culture has all but disappeared: "There used to be more than sixty different styles of classic rowing and sailing boats in Venice, and now there are less than fifteen. Nowadays, the majority are only used for sporting events. Although before they were the only means of transportation in the city. He continued that there was more to the inspiration behind Venice On Board than just sentimentality. Many Venetians find motorboats to be unsightly because they make noise and stir up the dirt that gives canal bottoms its murky brown hue. Rowers and sailors are more aware of their surroundings. He remarked, "It's a different rhythm of existence. It moves at a much more natural pace.

The club's main objective has always been to revive the use of traditional vessels among Venetians. But over the past few years, Venice On Board has been teaching its knowledge to roving tourists. This is great news for independent tourists like me since it gives us a rare chance to explore the city, especially the lagoon, the 212-square-mile enclosed bay that encircles Venice's downtown.

The breathtaking city of Venice built on water. Sailing down the Grand Canal is like a trip through centuries of Venetian history.#grandcanal #italy #venice #italian_places #italia_landscape #italiainphoto #thamesbarrieropark #londoncityairpor pic.twitter.com/WUMKVhjJbI

— Ilvolo Restaurant (@ilvolo_e16) July 23, 2018

The largest wetland in the Mediterranean, it is separated from the Adriatic by thin barrier islands and spits of land. It is shallow, marshy, and difficult for foreigners to travel on their own. Only 14 of the 62 outer islands of the lagoon can be reached by vaporetto, or water bus, and only a few of those, like the beach-lined Lido and Murano, which is renowned for its glassblowing studios, see frequent visitors. Numerous islands that can only be accessed by private boat are still present, along with vast stretches of breathtakingly gorgeous coastal marshes that are surrounded by wisteria and home to flocks of pink and silver flamingos and silver herons.

My partner Anna, a Venetian who can trace her ancestry to one of the 16th-century doges who controlled the maritime republic and were known to sail the lagoon in a golden ceremonial barge, joined me on this journey. She offered to take me to the secret pubs, or abkari, that she frequented while she was a student of philosophy. I took on the responsibility of showing her parts of her hometown that she had never been to in exchange.

The San Clemente Palace Kempinski Venice, which is situated on a little private island in a former monastery with its own fresco-filled 12th-century chapel, was the ideal aquatic base I had discovered for us. Only eight minutes by launch from the tourist-heavy Piazza San Marco, we felt as though we were entering an alternate universe of quiet and tranquilly as soon as we stepped into its gorgeous pier. We observed that the monks had outstanding taste in properties. In the chapel, marble cherubs danced above contemporary blown-glass sculptures by Venetian artist Lino Tagliapietra. The Kempinski's centuries-old garden offers exquisite lake vistas from every angle, which are now enhanced with abstract artworks. The only sounds we could hear while enjoying the sunset and an Aperol Spritz outside were the lapping of the waves and the cawing of seabirds. Which heavenly body is this? Anna thought of Dante's Paradiso.

The following morning, I ventured out for my first session at Venice On Board while Anna visited the Venice Biennale, an annual international art fair that takes place in the city from late April until November. Simon boiled down the technique of rowing into four movements that I repeated over and over to myself like dance steps as we sipped our espressos in satisfaction. I recited the following commands while standing in the middle of the deck: "gira," which means to rotate the oar backward, "like revving a motorbike," "spingi," meaning to dip the oar, "Talia lacquer," meaning to cut the water with a smooth stroke, and "torna" (rotate the oar back to its original position as it exits the water). Simon was steering and rowing from the stern. (Traditional boats are propelled by two or more oarsmen, as were gondolas until a revolutionary hull design made it possible for a single gondolier to propulsion and steering.) As I performed the four moves, Simon remarked, "You can obtain great outcomes with a minimum of effort. Remember, the Venetians used to do this all day long!

I rowed down the Rio Della Misericordia while Simon led us through a throng of racing water taxis and ponderous cargo barges, fighting the impulse to break into a performance of "O Sole Mio." He observed, "It's not like English rowing, in flat, peaceful lakes and empty rivers. Traffic congestion and tight curves are common in Venice. I discovered that the activity is a social event because of the leisurely pace. Simon cried, "Noon!" as we went below a bridge. Grandpa! He then took a break to discuss the Sunday family lunch menu with a stylish silver-haired relative. Simon stated, "I was born and reared in Cannaregio.

However, when we turned along a small side canal, the commotion died down. I was able to really settle into a rhythm in the solitude. As we continued to glide, Simon observed, "It's extremely meditative. I discovered that shouting "Oe!" followed by either premade (on the left, in Venetian dialect) or staged at blind corners would signal other vessels that we were approaching (on the right). In order to better maintain my equilibrium, I also learned to look straight ahead rather than at my oar when it dipped in and out. This gave me the opportunity to appreciate Venice's palazzos' exquisite architectural elements from the water's edge. This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see exquisite statues of boars' heads arranged in rows, ornately carved doorframes with stone steps leading down to the water, and rusted gates that concealed secret overgrown gardens because many of the side canals have no footpaths and can only be explored by boat. Since aristocracy would come by gondola, these used to be the palazzos' primary entryway. We now enter through the alley's servants' entrance. Everyone in Venice forgets.

When we entered the Grand Canal, where the water was churning like a washing machine from all the motorboats, the peaceful old-world ambiance abruptly evaporated. An ambulance boat once sped past with its siren on full blast, causing huge waves smashing over our bow and threatening to throw me over the edge. Simon laughed and remarked, "You are experiencing the complete Venetian water experience today.

He said, "Congratulations!" as soon as we finished the obstacle course. "You've made your first crossing of the Grand Canal!" He thought it would be the start of many similar trips.

The following two days, I spent with Anna in our island monastery honing my Italian nautical phrases while also looking for intriguing locations like Arana, a private museum of marine antiquities situated in a boatyard that was in operation from the Renaissance until 1920. It was jam-packed like an attic with fascinating artefacts, including a rare gondoletta, or small gondola, designed for two people.

I had been addicted to the water at this point and was eager to learn how to sail. The Venetian dialect, which differs almost as much from the official Italian I had studied in college as French does from Spanish, was given by Anna, who was eager to join me, as a means of translating the obscure nautical phrases.

Nicola Ebner, a statuesque man who had worked as a glassblower in Murano before quitting his day job for life at sea, would be the instructor this time. He is another club founder. Ebner was already loading the topa with a mast and canvas when we got there at nine in the morning. He announced that our destination would be the deserted island of Sant 'Andrea, which could only be reached by private boat and was crowned by a dismantled military fortification from the 16th century.

We began rowing through the canals of Cannaregio. We saw one of Ebner's buddies repairing a damaged outboard motor as he worked close to the residence of the 16th-century painter Tintoretto. "The engine never breaks if you row," When the man screamed out for assistance in fixing it, Ebner remarked, chuckling. (Ebner slowed down to describe how a plugged tube may be cleared using wire.)

Ebner paused in the last canal and demonstrated to me how to convert the topa from a rowboat to a full-fledged vela al torso sailing vessel by raising the sail, or torso, a special design with four uneven sides that can catch every breath of wind, erecting the wooden mast, fitting ropes, and lowering the sail. The handmade pieces fit together flawlessly, much like in a model aircraft kit, demonstrating the excellent craftsmanship. The canvas swelled, the mast creaked, and soon we were skimming into the lagoon's broad seas.

That moment was thrilling. The lagoon's sky seemed as big as Texas after the maze of urban rivers. Anna performed a traditional Venetian ballad between two courting lovers as she basked in the sunshine and space: "Marietta, jump in the gondola. The young man exclaims, "I'll take you to the Lido!" to which the person he is infatuated with mockingly responds, "I don't trust you! Too much of a scoundrel are you.

Ebner rapidly guided us through the fundamentals of adjusting the canvas and rudder to control speed and direction. He noted that, in contrast to modern boats, when the sail was tightened, the prow faced the wind, but when it was let out, the wind came from behind and enhanced our speed. He instructed me to adjust the sailing line and tiller with the same hand as we sailed through the mirror-flat, silver-blue waves. Ebner remarked with joy as we went past the wooden poles tied together that indicate the "lanes" excavated for motorized boats, "Look, we are heading beyond the broccoli."

The lagoon is just around six feet deep in certain places, thus Venetian sailboats were made with flat-bottomed hulls and detachable rudders to allow for greater maneuverability. However, Ebner noted that it is also feasible to sail vela al torso in the choppy waters of the Adriatic and elsewhere. In fact, the creators regularly sail a topo (a larger version of a topaz) to Croatia for a week-long voyage during which they all spend the night on deck.

Anna helped me improve my vocabulary as we relaxed into the journey and sailed sottovento (below the wind) as opposed to sopravento while we were in complete stillness (above it). She remembered an old Venetian saying her mother had used: "Sottovento via!" which roughly translates to "go under the wind and go," moving discretely in order to avoid being seen.

We got close to Sant 'Andrea, our destination, an hour later. We anchored up beneath a stone balustrade and climbed up to dry ground because there were neither docks nor even ladders. The island is currently as wild as a national park because the fortress has been abandoned for a century. It had a ghostly feel to it as Ebner led us up an old stone stairs without guardrails, over a walk lined with thorny bushes, under collapsing arches, and along an overgrown road. Finally, we scaled a bastion from which the republic's artillery previously had a magnificent view of the entrance to the lagoon. The Lion of Saint Mark, the representation of Venice, was carved into the wall. Today, I was forced to admit that the bastion would be a fantastic location for a bar.

Ebner's expression grew gloomier. The fate of the island is currently up for discussion, and Venetians are concerned that access may soon be restricted. We had previously passed an island that had been bought by a private owner and is now home to a posh yacht club. He lamented, "We Venetians all used to go there as teenagers for parties and picnics. Even though it's still meant to be accessible to the public, if you fly over, people will chase you away and threaten to call the police. Sant 'Andrea's residents hope that it will avoid that destiny and become a park that everyone can enjoy, "with a bar here, certainly, but a bar everyone can attend!" Ebner groaned: "I'm not hopeful,"

As soon as we resumed sailing, we forgot about this depressing note and once more joined Venice's vibrant maritime community. Shortly after we cast off, an old man dressed in hunter's camouflage drew up next to us in a motorized dinghy carrying a fishing rod load. He said, "How much did that sail cost you? The man identified himself as Giovanni Nackara, one of just two traditional sailmakers still in business in Venice, when Ebner told him. Nackara accepted the fact that his rival had created our sail with good humor. It still has a nice appearance. After griping about his morning's fishing success ("It's lunchtime and I haven't caught a thing. Nackara responded, "I want to sell Ebner a traditional boat that I no longer use. In fact, I almost got a ticket from the water police for fishing in the incorrect location!" After exchanging phone numbers, Nackara accelerated away.

This might be a good thing, Ebner said. "The pricing is right."

He had some thoughts regarding Venice's future after the encounter. He said, "This city might be the global leader in environmental sustainability." We could all simply row two or three persons in a typical rowboat around Venice. It can travel more quickly than a vaporetto without generating any pollution at all! It's a crazily idealistic vision, similar to the notion of restricting all traffic to Manhattan to bicycles, but as we swept across the lagoon's waves in the balmy spring sunshine, it was impossible not to daydream.

Where to Stay in The Floating City

San Clemente Palace Kempinski Venice: Staying at this opulent 196-room resort on an own island is the best way to see the size of the lagoon. Guests can take a five-minute boat journey to get to the Piazza San Marco.