Andrew Sessa and his brother visit Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater for a reunion and discover shocks — as well as an unexpected sense of familiarity — within the renowned walls of the structure.

Fallingwater is first heard before it is seen. Given the name of the mansion and its location over a cascade of a rushing stream, this should not have shocked me, but it did. With my architect brother Ben, I made the trip to the Frank Lloyd Wright-built house in Pennsylvania. We had always wanted to make this trek as Wright devotees.

As Wright had meant, the brook murmur burst up the curving, tree-shrouded driveway before we caught our first glimpse of the house. When the house was finished in 1937, his client, the retail magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann, would have seen this gradual unveiling.

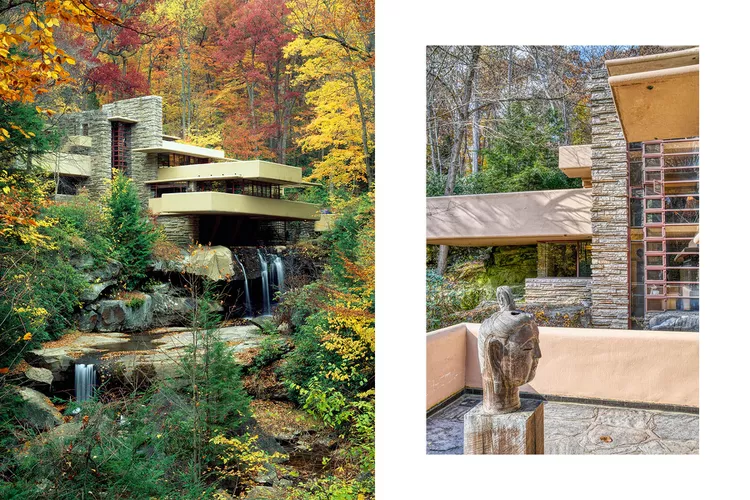

Even for a Wright enthusiast like me, the structure was practically unrecognizable when it finally came into view at the end of the winding route. Ben and I were shocked by the masterwork we had assumed we knew so well from pictures. Images of the house depict it to teeter and tower over the falls, with its terraces pinwheeling out from a four-story column, dating back to a Time magazine cover featuring a drawing of it in the background of a photograph of Wright in 1938. But Fallingwater initially appeared long and low when viewed through the trees. Its magnificently cantilevered concrete terraces and stacked sandstone walls all projected outward. It appeared to be hunkered down in the hillside and was reaching horizontally rather than upward.

Wright and the curators who now look after the house are both too savvy to have given away the ideal vista so early (and have since 1964, when it became the first house from the Modernist movement to open as a museum). Ben and I discovered throughout our tour that this unexpected magic trick was just the first of several that Wright used in his creation.

The pandemic, our weddings, the birth of our three children (Ben had two, I had one), and other life events caused us to repeatedly postpone our vacation to this primarily uninhabited area of southwestern Pennsylvania. Ben had traveled from New York City, and I had come from Boston, so when we eventually met at the Pittsburgh airport, I realized we hadn't spoken to each other since the pandemic started. My younger brother wasn't a kid anymore—I'd almost forgotten that.

We hopped in a rented car and traveled an hour and a half south through forested hills. We had a cathartic session about the difficulties of parenting before discussing how we first became interested in Wright. Was it a trip to the Upper East Side of Manhattan's spiraling Guggenheim Museum or the neighboring Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Wright's Francis W. Little House's living room is on display? Ben hypothesized that it might have been the stained-glass windows featured on mouse pads and mugs from museum gift shops.

I became aware during the chat of how commonplace the architect's plans are. Our admiration of their brilliance—the way each building blends natural and man-made materials, modern and classical notes, shape, and function—seems to have been absorbed almost by osmosis. Even though we had never even been there, we had seen that famous picture of the mansion above the falls so frequently that we almost felt like we had been there.

After a lackluster initial impression, we were led by our tour guide, Galen Miller, to the main entrance, which architect Frank Lloyd Wright incorporated into what appears to be the back of the home. I entered the room and was met with an immediate feeling of constriction. We entered a lobby characteristic of Wright's architecture: stone walls, low ceilings, little square footage, and poor lighting.

The open-plan living and dining area three stairs above had more space, but the ceilings were still reasonably low. Miller explained this was also intentional: "It forces you to look out, not up." Despite the wonders inside, such as the boulder that emerges from the ground to serve as the hearthstone and the Kaufmanns' orange-red, spherical cast-iron kettle above it, we couldn't help but look out into the woods through the windows that wrap around each corner, admiring the native rhododendrons and trees beyond.

My entire body felt drawn outside by the architecture. A hatch gave access to a ladder that descended to a platform over the stream, and glass doors opened to terraces with views of the waterfall.

Miller led us to the previous family's bedrooms. Standing on the gravity-defying terraces, these areas had a more cocoon-like feel than they did compressed spaces, providing intimacy, seclusion, and refuge from the wilds of nature. Ben and I were in awe of Wright's ability to seamlessly combine the inside and the outside and other parts of the building's architecture and interior design, such as how railings were transformed into planters and window muntins into display shelves. Everything in the structure fits into each corner like the parts of a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

Taking in these particulars made me think about how much Ben and I enjoyed the home museums our parents took us to when we were younger. Visiting the mansions of the Astors, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts always had a voyeuristic element but also had a soulful one. Their residences reminded us that even the most well-known people had flaws and were similar to us.

Which one is your Favorite Season? 🍃

— Santa Fe (@SantaFeCdmx7) August 11, 2018

Fallingwater House in Pennsylvania designed by Frank Lloyd Wright pic.twitter.com/nusiFB4aWP

Thanks to the tours, we gained a greater understanding of the linkages between people's decorating styles and way of life. We were so interested in the connections between a home and its owner, style, and way of life that they finally inspired us to pursue careers in design, travel writing, and architecture, respectively. We grinned at the assortment of walking sticks and the tiny footbath with a fountain outside the front entrance, which the Kaufmanns had asked for so they could clean up after their nature walks. Miller pointed out the white wisteria Edgar Kaufmann's wife, Lillian, chose for the trellis surrounding the guesthouse, and I was reminded of the fruit trees our grandfather had planted to help him remember his native Italy.

After the trip, Ben and I ventured downstream to a secret overlook that offered the picture-perfect panorama we had pictured. We went down a wooded trail before turning around to see the house from the base of the falls as we had before. It didn't appear easy, like a Jenga tower, because it was set above the stream.

I could see why Wright didn't want people to be able to see this view right away. You can only comprehend it by living there, by going up the stairs and through the rooms. After you've been inside, it takes on a life of its own and is infused with the dynamic architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and the family's character.

Our parents sold the home where Ben and I grew up not long before the epidemic. I wanted our home to be maintained as a museum so my son could learn more about his dad's life by visiting the home he grew up in, as I was looking back up at Fallingwater.

At the same time, I recalled that although the house was essential to us, the solid, long-lasting, and — perhaps most significantly — movable relationships created within it were even more significant. Wherever we go, those endure. I asked Ben what his favorite part of the vacation had been as we headed back to the airport, and he responded without missing a beat: "Spending time with you."