In Chicago, there is always art nearby—in subway stations, pedestrian underpasses, neighborhood museums, and city parks.

I left my home in the South Side of Chicago, near the green Hyde Park and Kenwood districts, one day in June to go for a stroll with Adrienne Brown. Brown, a colleague at the University of Chicago, focuses on how race is perceived in design. We intended to examine the paintings that span about a mile of the underpasses in our area.

Black, Latinx, and Indigenous artists have created a large portion of the public art in our area, and their work has become increasingly important throughout the past five years of political unrest and the epidemic. While I still enjoy visiting those opulent halls and galleries, the South Side is a world away from downtown and the North Side's cultural institutions. These days, however, I tend to look for artwork that conveys a sense of movement more frequently. Migrations have shaped Chicago's history: the Great Migration of Black people from the American South; the immigration of people from Mexico, which has resulted in the city having the second-largest population of Mexican Americans in the nation; and the return migrations of Native Americans, who were forced into exile and came back to work here.

Brown and I paused in front of a painting of Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, a Black trader from the African diaspora who is thought to have been Chicago's first non-Indigenous settler, at the 47th Street Metra underpass. A residence built by DuSable and his wife Kitihawa, a Potawatomi tribeswoman, in the 1780s opened a new chapter in the history of the settlement. DuSable's head is depicted in the mural, which was created by the Chicago Public Art Group in 2008 with lead artist Rahmaan Statik Barnes. He focuses on a street map with a red circle that says THERE YOU ARE.

Brown and I could hear the traffic on what was once known as Lake Shore Drive but was renamed Jean Baptiste Point DuSable Lake Shore Drive in 2021 while we stood there. When Brown said she'd found that many architectural students prefer to work on public projects under underpasses, I started to consider the various histories that a city's streets contain.'

She replied, "That's where the memory is," and I imagined a flow of memories—those of the city and the individuals who had come this way—accumulating and pooling in the cooler air where we were standing.

Brown and I continued through the underpasses, a lengthy gallery of pictures, on a sunny day while we chatted about how urban environment can function as a sort of archive. We examined Childhood Without Prejudice by William Walker, a historical work, and Olivia Gude's magnificent Where We Come From...Where We're Headed, a 1992 mural, both located near 56th Street and Stony Island. At this intersection, Gude halted traffic and painted delicate full-length portraits of onlookers as well as their responses to her queries.

"I come from the Englewood neighborhood. There, it's incredibly difficult."

"The struggle of going back to school after thirty years and all the joy I get walking through Hyde Park in the spring."

"I basically came from a life of disaster. I'm tuned in now. Now I'm just practising my religion."

"From where are you coming? " Gude had made a query. Where are you headed? These are the kinds of questions that public art frequently wishes to pose to onlookers; on occasion, it can be simpler to hear and respond to them outside.

On another occasion, I took a stroll to the Hyde Park Art Center, which has a long history of identifying and promoting artists from all over the world. The current exhibition, "Planting and Managing a Perennial Garden: Shrouds," by Chicago artist Faheem Majeed was visible through the main gallery's industrial garage doors.

Majeed's pandemic-era fabric rubbing of the South Side Community Art Center's façade billowed upward to a height of almost three storeys. With assistance from the Works Progress Administration, the SSCAC was established in 1940 and is situated in Bonneville, another South Side neighborhood. It is committed to upholding its own tradition and supporting burgeoning African artists.

What’s Next For Chicago’s Art And Culture Scene https://t.co/twIwHVPId9 pic.twitter.com/GKGoM6XppG

— Top Lifestyle News (@topstylenews) November 18, 2022

You can see the brickwork and window frames, nail holes and crumbled mortar in Majeed's meticulously rubbed graphite lines—details that are recognizable to the artists who have laboured inside SSCAC's walls. Some of these young artists, like the printer and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, the photographer Gordon Parks, and the painter of the Chicago jazz scene Archibald Motley, went on to achieve widespread fame.

Majeed has extensive knowledge of the structure as he served as the SSCAC's director for six years. He gently changed his response when I asked him whether he had discovered anything new about it while performing the rubbing. He claimed that the goal was not to create an artefact or to gather historical data "to touch the entire façade. We were attempting to duplicate a living entity."

Majeed and the curator Allison Peters Quinn value the ability of random visitors to enter the Hyde Park Art Center by keeping the doors unlocked.

Majeed explained, "I'm trying to get outside of the walls.

There are paintings all over the place in Pilsen, the heart of Chicago's Lower West Side: on storefronts, the side of a dentist's office, and in back alleyways. Hector Duarte, a Mexican-born artist, painted a giant with an extended arm reaching to the roof on the façade of his home at the junction of Cullerton and Wolcott. The giant's hands and face are covered in a twig pattern, and his fingers and limbs are unsettlingly bound by barbed wire. The song is referred to as Gulliver in Wonderland. Duarte has been a prominent presence in the Chicago scene for many years and studied under the famous Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. His house has a sign on one window that reads NOT FOR SALE.

I viewed an exhibition of the striking paintings by Carmen Chami of women who had immigrated to Chicago at the National Museum of Mexican Art, which is located a block north. Photos that belonged to Frida Kahlo and served as the basis for her portraits will be featured in a forthcoming exhibition. I talked with the NMMA's chief curator, Cesáreo Moreno, about if there is a particularly Chicago approach of making portraits, and he highlighted artists like Kerry James Marshall, Barkley L. Hendricks, Dawoud Bey, and Charles White, whose works he sees as being similar to those in murals. He claimed that they are united by their "attention to the common person, the everyday worker, and the folk hero."

I was in the museum when a dazzling painting by Mario E. Castillo, who was born in the northern Mexico state of Coahuila and later emigrated to Chicago in the early 1960s, caught my attention. It was titled The Ancient Memories of Mayahuel's People Still Breathe. Castillo's bizarre surrealist artwork confuses the senses with its whirling eyes, corpses, Day of the Dead skulls, native Mexican vegetation, and feathered wings.

This enormous picture, framed only by the wall constructed around it, was first displayed in 1996 as a component of an exhibition honouring the history of Pilsen and the Little Village area. It appeared as though it was only stopping here for a short period before moving back outside.

As I made my way along 18th Street to view two outdoor murals by Chicago artist Sam Kirk, I had the impression that I was following some of the directions in its winding lines. Fierce, the first model unveiled for Pride, is a fantastic addition. Seven full-color persons with poses and fashions that seem both queer and normal are surrounded by a rippling rainbow ribbon that winds around white line drawings of figures on a black background.

A person wearing a turquoise outfit lifts a big brown hand at the very middle. From the bus stop across the street, onlookers took pictures while a woman stopped and mouthed the word "Wow." One of my favourite Kirk paintings is just a short distance away at 16th and Blue Island. Sandra Antongiorgi and I collaborated on the 2016 piece Weaving Cultures, which features five towering visages of regular, lovely women who are carrying their histories in their faces.

Public art and Chicago's keen architectural sensibility go hand in hand, but when you get to the Loop with its crowded buildings, stores, and museums, the public art doesn't have as much room to breathe. The back of the Chicago Cultural Center is covered in Kerry James Marshall's 2017 mural Rushmore, which was painted by Jeff Zimmermann based on a painting by Marshall down a narrow lane that feels more like an alley. It depicts the portraits of 20 women who have made significant contributions to Chicago history, including Oprah Winfrey, poet Gwendolyn Brooks, novelist Sandra Cisneros, and artist Margaret Burroughs. Their faces resemble tree trunks that extend upward towards a banner-draped sky that cardinals are holding aloft.

Marshall is a well-known figure in Chicago, so when I went there, I was sorry that the mural wasn't situated so that it could have a meaningful interaction with the public. Instead, a worker wearing a yellow reflective vest and a man dressed in faded clothing both made conscious attempts to avoid being in the path of my camera.

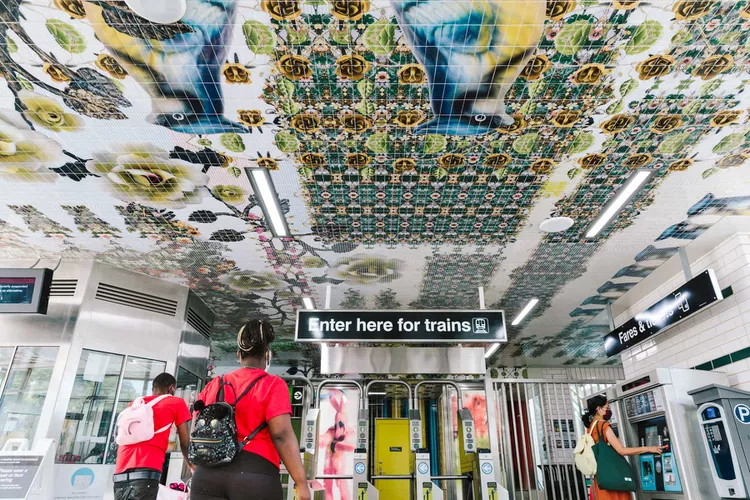

I recalled how it had been simple to feel happy when I had seen the stunning tile and glass-screen installations of vines, birds, floral motifs, and textile costumes that Nick Cave and Bob Faust had created across the Garfield Avenue CTA stop a week or two earlier on the South Side. ........... ......

I crossed Michigan Avenue from Rushmore into Millennium Park, passing Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate, a circular silver icon that was polished by Local 63's ironworkers and that captured the metropolis and its visitors in its undulating surface. I kept going across the elevated skyway until I reached the Chicago Art Institute. A magnificent exhibit of massive metal sculptures by renowned Black sculptor Richard Hunt, who was born on the South Side in 1935, was shown on the roof.

I observed that every temporary display area was filled with the creations of artists of colour within. The portraits of the Obamas by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald from the Smithsonian, the landscape drawings by the Black and Native American artist Joseph Yoakum, a self-taught topographical genius, and, in the galleries typically reserved for sizable exhibitions of European art, a collection of profound quilted portraits by Bisa Butler.

I should look at Eldzier Cortor's 1948 picture, The Room No. VI, which depicts two people and two children attempting to sleep in a bed that takes up the majority of the room in a small apartment. This suggestion came from Sarah Kelly Oehler, the museum's curator of arts of the Americas. She noted that it would be a contrast to Marshall's Rushmore since it depicts "anonymous women in an intimate place."

As Cortor put it, "the confines of the same four walls in a condition of extreme poverty," The Room No. VI is a painting of remarkable formal creativity and a profound knowledge of that situation. It's a work that would fit in just fine at the SSCAC, which has an Eldzier Cortor Gallery, just as Cortor himself did. As I moved on to the next room and observed Motley's 1943 Nightlife, Catlett's linocut 1952 Sharecropper, and White's 1951 lithograph Gideon, I had the thought that these museum galleries had attempted to recreate a long-held and cultivated perspective on art that was located about 40 blocks away, in Bronzeville.

The Field Museum's coordinator for Native American community involvement, Debra Yepa-Pappan, is a Jemez and Korean artist. The Field has enormous collections of art from all over the world in addition to its enormous halls filled with dinosaurs and elephants. For the past few years, the Field has been attempting to honour the works and their creators while acknowledging the exploitative ways these pieces frequently entered the museum.

Yepa-Pappan led me through the Native American Exhibition Hall, which has been completely redesigned and will open in the spring of 2019. She described the ideas for the new exhibits as we stood side by side in the still-dark construction area. The co-curators from various tribes who are part of the advisory board preferred stories, voices, and a tangible sense of significance to glass cases filled with relics. In response, the Field is introducing new pieces by contemporary artists while reducing the exhibits from over 1,600 objects to only 250.

A segment of the hall will be devoted to Chicago and the Great Lakes, with the remaining sections rotating to highlight other parts of the nation. The hall will be structured around five tales. These initiatives heavily rely on technology, including conversations that have been recorded and films that provide context. The orientation towards the future and away from nostalgia and the past may be most significant.

Collaborations with Native artists and curators were fostered by Alaka Wali, the Field's curator of North American anthropology. Her strategy avoids portraying Native cultures as "fossilised in time" and treats Native-made objects as works of art rather than historical artefacts. Wali wants this strategy to influence how other museums frame their holdings.

Both Wali and Yepa-Pappan advised me to visit downtown to see the brand-new banners by Grand Portage Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson on Chicago's vibrant Riverwalk, a destination for tourist cafés and architectural boat excursions. A few days later, I went and stood on the DuSable Bridge, remembering Kitihawa, thinking of the portrait of DuSable in the underpass in my neighbourhood, and feeling at peace. There are five large banners there, the first two of which read in Potawatomi: Bodewadmikik Éth Yéyék, which is translated over the last three: YOU ARE ON POTAWATOMI LAND.

Arkee Chaney, a 77-year-old artist, and I were standing next to the DuSable Museum of African American History in Washington Park on Juneteenth 2021. As part of the Prison+Neighborhood Arts Project, we were painting a mural that had been created by artists who were incarcerated. Each of us was holding a brush and a cup of paint. I learned how to keep my hand steady against the board from Chaney. if you are looking for a good deal, a savvy, a savvy, and a savvy, and a

Chaney revealed to me that he studied Margaret Burroughs for 31 years while he was incarcerated. He said, "I adored her. "She was a mother figure. For me, Grandma always had colours and paintbrushes." Burroughs was a visionary who not only played a key role in establishing the SSCAC but also the DuSable, the nation's first museum dedicated to African history and culture. She thought that art ought to be shared.

She sent him upstairs to photocopy her prints for people she liked, according to Majeed, who worked with her at the SSCAC. The DuSable houses a collection of Burroughs' linocuts in addition to historical exhibits and artwork created by some of her imprisoned students. Occasionally, as as on Juneteenth or when there are special outdoor performances, there is a joyous crowd; on quiet days, you can view these with only a few other, intentional visitors.

A few weeks later, when I stood at the intersection of 37th and Langley to view the recently unveiled memorial created by sculptor Richard Hunt to honour writer, anti-lynching crusader, and educator Ida B. Wells, I was reminded of legacies once again. The elaborate, curved, pointed bronze sculpture known as Light of Truth soars 20 feet into the air. There were a few more individuals there to honour Wells and Hunt; the mood was brave and reverent. Majeed later told me, "That is a beacon.

A summer of neighbourhood walks and initiatives, curators, paint, movement, and working in public. A place to think and look skyward is Light of Truth. Hunt has a superior understanding of how to focus Chicago's metallic architectural language, the city's challenging history, and the power of its prairie sky.